BICS vs. CALP: What Every Teacher Needs to Know to Support English Language Development

Ever wonder why some English learners seem fluent in conversation but still struggle in academic classes? If you've noticed this phenomenon in your middle or high school classroom, you're observing a critical distinction in language development. That sophomore who confidently chats with peers at lunch might still find her biology textbook overwhelming—and there's solid research explaining why.

The BICS vs. CALP Framework

Research shows that Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS), or social language, typically develop within two years of exposure to the English language. However, Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) takes approximately 5 to 7 years to fully develop (Hill & Björk, 2008).

This gap is especially significant in secondary grade classrooms, where academic content becomes increasingly abstract and specialized. While your English learners may sound fluent in the hallway, they're still building the academic language proficiency needed to access grade-level content in your classroom.

Understanding Cummins' Quadrants

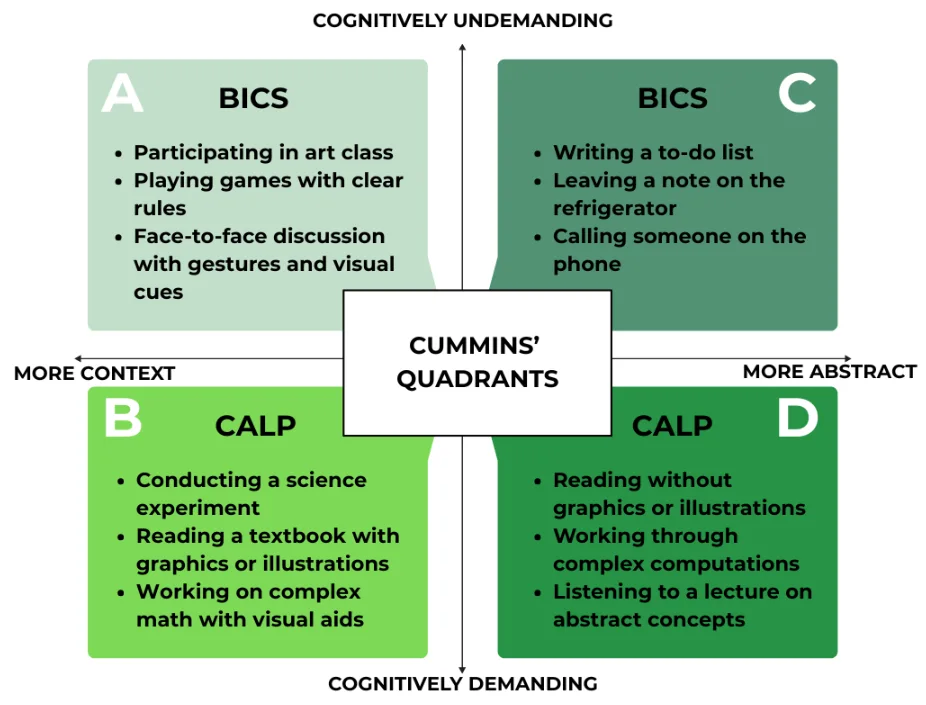

Dr. Jim Cummins, a renowned researcher in multilingualism, explained this phenomenon through his framework that categorizes learning activities based on two dimensions: cognitive demand and contextual support (Cummins, 2008).

These four quadrants help us understand where different classroom activities may fall:

- Quadrant A (Context-rich, low cognitive demand): Participating in art class, playing games with clear rules, face-to-face discussions with gestures and visual cues

- Quadrant B (Context-rich, high cognitive demand): Conducting science experiments, reading textbooks with graphics or illustrations, working on complex math with visual aids

- Quadrant C (Context-reduced, low cognitive demand): Writing a to-do list, leaving a note on the refrigerator, calling someone on the phone

- Quadrant D (Context-reduced, high cognitive demand): Reading without graphics or illustrations, working through complex computations, listening to lectures on abstract concepts

We see that CALP-related activities primarily fall in quadrants B and D. In other words, typical secondary-grade activities, such as analyzing The Crucible or listening to a lecture about cellular respiration, require students to access specialized, abstract academic language with varying levels of contextual support.

Three Practical Strategies for Supporting Academic Language Development

1

Make Input Comprehensible: The Think-Aloud Strategy

When introducing new academic concepts, use the think-aloud protocol while demonstrating problem-solving or text analysis. Verbalize your thinking process while using gestures, drawing diagrams on the board, and pausing to rephrase complex ideas in multiple ways. For example, when teaching quadratic equations, don't just solve—explain each step aloud while color-coding parts of the equation and connecting abstract symbols to visual representations. This moves abstract content from Quadrant D toward Quadrant B by adding contextual support.

2

Support Reading Comprehension: The Preview-Vocabulary-Visual (PVV) Routine

Before assigning content-area reading, implement this three-step routine:

- Preview: Activate background knowledge by showing images, videos, or real-world examples related to the topic

- Vocabulary: Pre-teach 5-7 essential academic vocabulary words using the Frayer Model (definition, characteristics, examples, non-examples)

- Visual: Provide graphic organizers or illustrated glossaries that students can reference while reading

This approach is particularly effective for middle and high school English learners because it builds the conceptual foundation before they encounter complex text.

3

Support Reading Comprehension: The Preview-Vocabulary-Visual (PVV) Routine

Create discipline-specific sentence frames or sentence stems that incorporate specific academic language. Instead of asking students to "explain cellular respiration," provide fill-in-the blanks scaffolds like:

- "During cellular respiration, _______ is converted into _______ through the process of _______."

- "This process is important because _______."

- "The relationship between _______ and _______ demonstrates _______."

These frames and stems provide English learners with the syntactic structure and academic vocabulary necessary to express sophisticated content knowledge while still developing their CALP.

Helping English Learners Access Academic Content

Remember: Fluency in social language does not necessarily indicate readiness for academic content. Make sure to include intentional adjustments that add contextual support and scaffold cognitive demand during instruction. With the right knowledge and tools, every content teacher can support English learners' academic language development and success.

Sources Cited

Cummins, J. (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In B. Street & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Language and Education (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 71-83). Springer.

Hill, J. D., & Björk, C. L. (2008). Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners. ASCD.

About Language Tree Online

Language Tree Online provides standards-based, multisensory resources specifically designed for middle and high school multilingual learners. Ready to boost English proficiency AND academic achievement? Learn more about our resources that help you implement these strategies in your classroom.