Focus on What Matters Webinar: What to Teach ELLs of Varying Levels

As ELD educators, one of our most important responsibilities is imparting our English language learners with the language skills they need to succeed – both in and outside our classrooms. At our recent webinar, three veteran ELD educators shared insights gained from decades of experience working with ELL students at all levels. The panelists discussed:

- Essential skills needed at different proficiency levels

- Effective strategies for skill development

- Types of tools and resources for various proficiency stages

- How we know when students are on the right path

Sandra Peñaloza

- Administrator of Instruction, Innovation & Improvement

- Alternative Education, Dept. of Student Programs & Services

- Riverside County Office of Education (CA)

David Noyes, NBCT

- National Board Certified ELD Educator with over 30 years of experience

- Evaluator for the English Language Proficiency Assessment of CA (ELPAC)

Margaret Towner

- Director at MD Educational Services

- Specialist in Literacy Diagnosis and Intervention

- Expertise in English Language Acquisition

In this blog, we outline the key takeaways from this illuminating discussion.

Start with Identifying Students’ Strengths

All middle and high school English learners enter our classrooms with linguistic and cultural assets. This is coupled with unique experiential knowledge. Some ELLs can speak, read, and write fluently in their L1. Others have studied English as a second language in their native country. And others have gone through physical and emotional challenges we can’t even imagine.

Sandra Peñaloza, a senior administrator leading educational innovation at Riverside County Office of Education, drew from her 30+ years in education. She emphasized that educators should begin with a strength-based approach.

“Our students come to us with many strengths and skills. It’s our job to figure out what those strengths and skills are when they arrive in our classrooms."

She also notes that some of these strengths can only be observed or gathered through discussions with parents and other teachers, including:

- Oral language skills and vocabulary usage

- Cultural and linguistic assets

- Maturity and comfort with social interactions

- Resilience in the face of challenges

- Motivation – both intrinsic and extrinsic

Once you have this “informal data”, you then look at the “formal data” gathered through local and state assessments, writing samples, and grades in content classes. Make sure these are consistent and then use all of this information to provide a more holistic approach to the student.

Informal

- Teacher Observations and Teacher Interviews (Prior Teachers)

- Oral Language Interviews

- Classroom Performance Tasks

- Student Work Samples (Portfolio Assessment)

- Peer Interactions

- Parent Input/Insight

Formal

- Language Proficiency Assessments

- Measures of Performance in Content Areas

- Writing Samples (English and Home Language)

- Reading Comprehension

- Vocabulary Assessment

Sandra then talked about acknowledging that every student has a different starting point. Therefore, we should look at continuous progress over time.

“I always say this when I'm training teachers, instructional assistants, or principals, ‘We always want to focus on progress over time.’”

Understanding and acknowledging students’ strengths as well as where they are at in their stage of development is key to unlocking the desire to learn.

Peñaloza shared her own experience as an English learner in kindergarten. While Sandra was early in her English language development, she was already reading and writing in Spanish. Her teacher at that time did not know (or care) about this asset. As a result, Sandra was bored and, in her own words, "got into a lot of trouble".

It wasn’t until first grade that a teacher changed her life by recognizing her Spanish reading abilities and telling her, "You're so smart." This simple acknowledgment transformed her motivation.

Use ELD Standards as a Teaching Roadmap

After you have a firm grasp of your students’ capabilities and where they are in their language journey, the next question is where to focus your language instruction. David Noyes, who is the Head of Curriculum for Language Tree Online, emphasized the importance of using your state’s English language development standards (e.g., New York, California, Texas, WIDA, Arizona, etc.) as a roadmap for teaching ELLs at each level.

While these standards may seem overwhelming at first glance, they are worthwhile to study and know well. That’s because they answer the question of what you should be teaching by:

- Providing clear differentiation between proficiency levels

- Detailing the specific skills students should master at each level

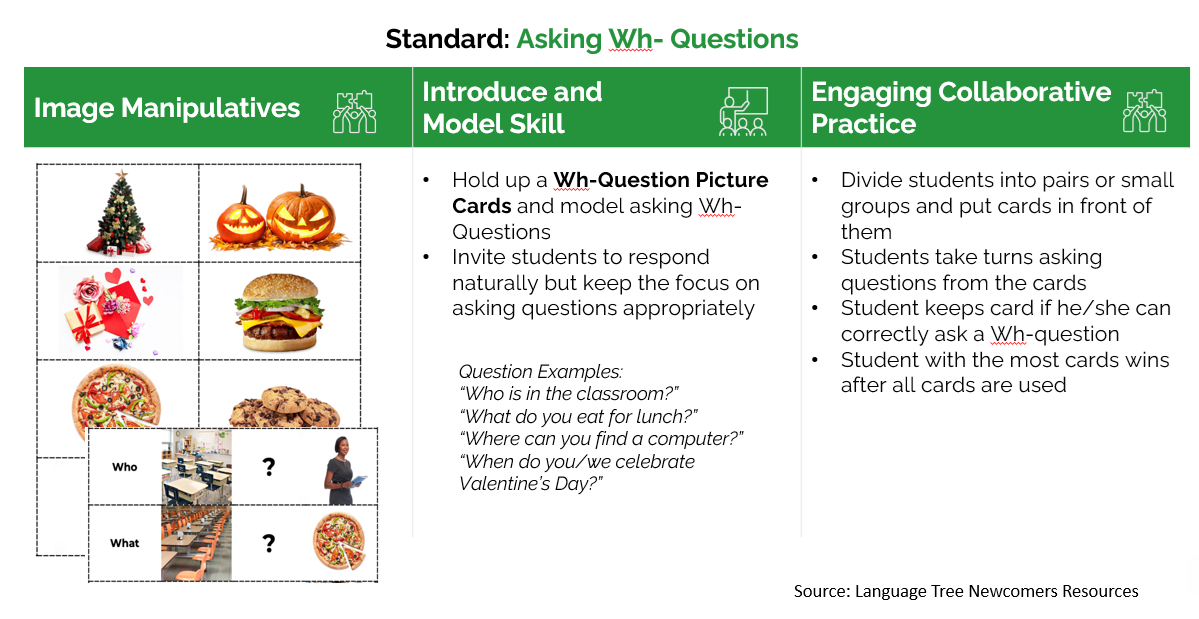

Using the example standard of "Exchanging Information and Ideas," he explained how the standard breaks down skills like asking and answering yes/no and wh- questions for Beginner-level students. Teachers can then integrate these skills with targeted instruction covering all domains: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

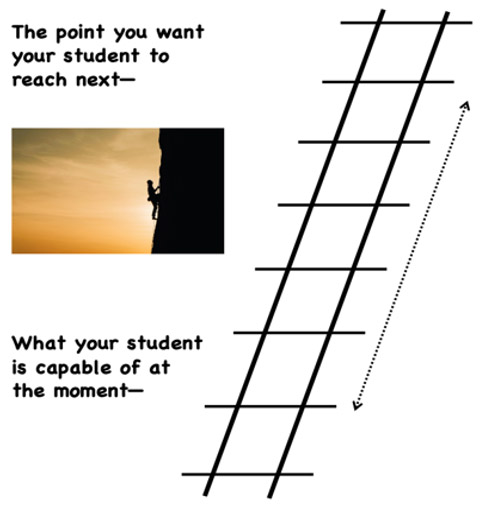

Scaffolding and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

Margaret Towner, a literacy specialist with expertise in language acquisition, spoke about the importance of scaffolding standards-based instruction. She highlighted the value of Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development, a framework that helps teachers gauge whether their instruction is appropriately challenging for each student.

Margaret Towner, a literacy specialist with expertise in language acquisition, spoke about the importance of scaffolding standards-based instruction. She highlighted the value of Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development, a framework that helps teachers gauge whether their instruction is appropriately challenging for each student.

According to Vygotsky's concept, successful language instruction requires carefully calibrating the difficulty level of tasks. Teachers must constantly ask themselves: Is the content too challenging? Too simple? Is it just right? This sweet spot allows educators to gradually advance students' language skills while maintaining engagement and confidence.

Margaret introduced ways to scaffold instruction to stay within students’ zones of proximal development. One of her recommended approaches for a mixed-level ELD class is looking at physical classroom organization so students have different language models around them and leveraging peer support.

- Vary seating for group work and small group instruction by language levels (different levels for group work and similar levels for small group direct instruction)

- Pairing newcomers with more advanced students to help them “decode” language and foster social integration

- Creating opportunities for students to hear varying levels of English

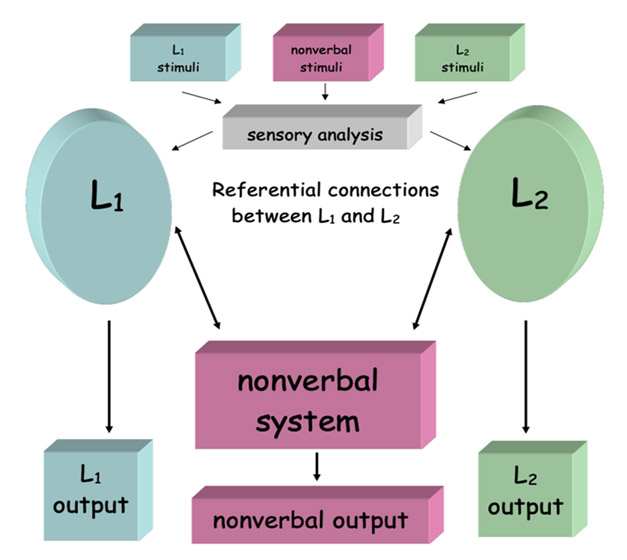

The Dual-Coding Approach to Language Learning

Another way to scaffold language instruction, especially for beginner-level learners, is through a multi-sensory approach. Margaret referenced Allan Paivio, a Canadian cognitive psychologist, who advocates for the use of visual, oral, or tactile sensory input and output in language instruction.

His Model of Dual Coding for L2 (second language) Language Acquisition emphasizes the connection between verbal language and symbolic language, such as:

- Visual meaning

- Spelling and word patterns

- Real-world objects (realia)

- Photographs and diagrams

- Linear arrays and thinking maps

If we provide multiple opportunities for students to “hinge” or pair their L1 or L2 knowledge with imagery, this will strengthen students' understanding of the new language. They can accelerate their learning by leveraging the brain's natural processing systems. When learning their L2, learners actively engage both their first language (L1) and nonverbal systems in parallel. These systems don't just operate independently – they integrate, creating stronger neural pathways for language acquisition.

“If we can match or hinge information back and forth and be flexible about it, then students have the tools to output their understanding through L1 or L2, or gestures and showing responses.”

In other words, offering students multiple pathways to express their understanding – whether through their first language, second language, or non-verbal responses – is an appropriate step for beginner-level learners.

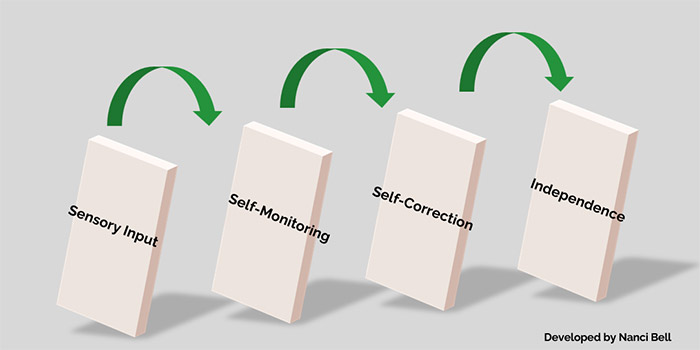

Bell's Cognitive Dominoes: The Path to Language Independence

Margaret then connects Paivio’s language development through multiple sensory channels with Nancy Bell's Cognitive Dominoes framework, which outlines the progression from initial language learning to language independence:

- Sensory input (visual, oral, tactile)

- Self-monitoring

- Self-correction

- Independence

A key component of this model is self-monitoring. Teachers can and should strategically intervene with questioning techniques to guide student learning. This scaffolded approach allows students to develop metacognitive skills while acquiring language proficiency.

Questioning Strategies

When students learn to self-monitor at stage 2, teachers can start to step in with appropriate questioning strategies.

“Is it this or is it that? Is that a boot or is that a slipper? Or something much more complex, like an idea in science. Then they can self-correct because they're at a conscious level of learning. From self-correction, the students can then go to independence. Self-correction carries them over into the capacity to be independent in their learning and not rely on the scaffolding that we often do during our instructional periods. “

The art of questioning evolves with students' language proficiency and can be scaffolded. Margaret recommends applying different questioning types and techniques based on ELL levels.

Questioning Strategies: Beginning Levels

- Yes/no questions

- Visual or text responses on cards

- Single-word responses

Questioning Strategies Intermediate to Advanced Levels

- Probing questions ("Can you tell me more?")

- Choice and contrast questions

- The five W's (who, what, when, where, why)

- Socratic questioning for advanced learners

Appropriate Resources and Tools for Each ELL Level

David Noyes then discussed the types of instructional tools and resources appropriate for each level. He provided an example of how he would scaffold instruction of the extremely useful language skills involved in“asking and answering questions” based on proficiency levels.

While this skill is familiar to newcomers, many have only practiced it orally in their first language. To learn how to ask and answer questions in a new language, David felt it was important to provide some visual context (in this case, through image-based manipulatives) along with opportunities for peer-to-peer collaboration. He also recommended these steps:

- Use vocabulary that students already know from home or school

- Front-loaded or review this vocabulary and attach it to the language skill

- Model the skill (for example, answering wh- questions) and explain what you’re looking for in their written or spoken answer

- Finally, provide an opportunity for pair or group collaboration

He described an exercise he used in the past for newcomers in his class:

“I divided the students up into pairs. I modeled that skill and I became the facilitator. Think of sheltered instruction activities like Kagan and SDAIE but really moving the students into the focus of collaboration and communication around that language skill or function.”

For students who are moving beyond that beginning to an intermediate level, it will look a little different. You can apply the same premise around introducing the skill, but it will be more in the form of a review because they've had exposure to wh-questions all day long in their content classes.

However, even for more advanced learner levels, it's still important to make connections to the skills. David continued to use a lot of collaborative opportunities, kinesthetic word cards, and questions. The difference was he added more complex tasks to apply the skill of asking and answering questions and brought in multiple content areas.

With long-term English learners (LTELs), we move toward even higher-level skills. The standards will be more complex. He looked at a reading standard around how prefixes change the meaning of a word. In this example, he allowed his students to use a graphic organizer containing prefixes. Students also had language logs where they were writing down these newly learned prefix meanings and applying these connections to words they’ve seen before or that they're already using. Then he wanted to contextualize it by bringing in multiple content areas and providing writing opportunities using prefix words which students can do online in the Language Tree program or on a printable writing task.

Measuring Progress and Assessing Competency

The last question to the panelist was how do we know if our ELL students are truly progressing?

David emphasized that language development is a continuous journey that requires different approaches for different proficiency levels. For newcomers, his focus often begins with listening and speaking skills, using speaking rubrics to track progress. However, as students advance to intermediate levels, his instruction shifts to integrating all four language domains - listening, speaking, reading, and writing - while incorporating content from various subjects like science, social studies, and math.

Sandra added her point of view as an administrator who often performs classroom walkthroughs and observations. She looks at both student-centered and data-based indicators for signs of progress.

Student-centered indicators, which can be observed, include:

- Independent use of scaffolds without prompting

- Organic participation in group discussions

- Ability to deliver and express their thoughts and opinions

- Self-advocacy skills and asking for feedback

- Engagement in Socratic seminars (back-and-forth questioning)

If you're observing classrooms, and you see that students are using scaffolds on their own without being told, that’s a sign they’ve got it. As they gain independence, students don't really need to go to the scaffolds that the teacher has provided.”

She believes a critical mind shift happens when students advocate for their education.

“When students ask questions like ‘What do I need to do to be able to pass this writing exam? What do I need to do to get reclassified?’ At that point, they also don't see themselves as English learners. That title goes away. They see themselves as just learners.”

In addition to student-centered indicators, you should look at data-based indicators, such as assessment scores and grades across all core subjects. Note that growth in assessment scores may be perceived differently by individual teachers so look to professional learning communities and teaching teams for the definition of growth.

There should be a match between assessment results, grades, and achievement levels. You can’t have poor grades and then be doing great on assessments or vice versa. There should be alignment and consistent movement toward grade level in all core subjects, not just English.

Conclusion

All panelists agree that supporting English Language Learners is a complex but rewarding journey that requires dedication, observation, and empathy. It starts with a positive, student-centered approach to English language instruction. Rather than focusing on “deficits”, educators should shift to an “asset-based” mindset of building upon students' existing knowledge and skills.

Every English learner begins from a different starting point. However, with an instructional roadmap based on the standards, scaffolding strategies, and school community support, students at any proficiency level can make progress toward language competency.

Finally, it's important to remember that language competency is a continuum - there is not a final destination. That means taking a long-term view of progress and celebrating small, achievable goals. Educators can help the process through continuous observational and data-driven monitoring. And by maintaining a strength-based approach at the core, we can help our ELL students achieve their full potential.